In your excitement about being in the world’s largest public square and making your way through Tiananmen (the gate) to enter the Forbidden City, you could be forgiven for missing these white marble columns, one on either side of the gate on the outside and two more on the other side of the gate once you do pass through.

These 10 metre high huabiaos date from the 15th century when the original Ming gate was constructed.

Huabiaos were originally used as road signs or as building aids in large construction  projects (their shadows providing long straight lines).

projects (their shadows providing long straight lines).

Over time the huabiao took on new roles and have a long association with Chinese royalty dating back to the time of kings Yao (c. 2356 – 2255 BC) and Shun (c. 2294 and 2184 BC). In these early times the huabiao was a wooden post erected in marketplaces and other public areas to solicit public criticism of the king and his ministers – slander pillars, if you like.

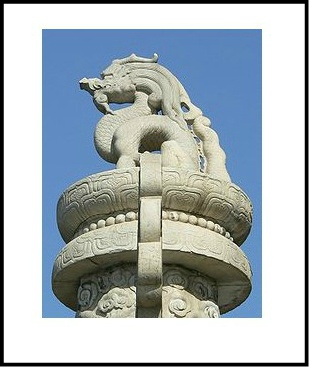

Wooden posts were replaced during the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) by stone or marble pillars which, over time, became more and more decorative and ornately carved and which became ornamental adornments of palace gates (like these ones at Tiananmen), imperial gardens and mausoleums.

Most assuredly the Ming and Qing emperors were not seeking peasant feedback via these huabiaos at Tianamen. The dragon carvings on the columns reminded the common people of the power of the emperor, lest they forgot and felt inclined to provide unwanted feedback.

While the four Tiananmen huabiaos were ornamental they had an important role in protecting and guiding the emperor. You will notice atop each of the dragon and auspicious cloud (the two prongs you see sticking out – cloud board) adorned columns a carved lion-like creature or a “heaven-gazing hou – wangtianhou ” sitting in a “dish for collecting dew.”

Looking more carefully you can see that the two hou outside Tiananmen look outwards while those on the inside look towards the Forbidden City – home of the emperors.

When the emperor was away from the palace, the outward facing hou watched over him and reminded him to return to the affairs of state should he linger too long through over indulgence with the common folk or through admiring the beauty of the mountains and rivers. The outward gazing hou came to be known as “watching for the emperor’s return” and the columns themselves, ‘watching columns’. The inward facing hou ‘expecting the emperor to go out’ reminded the emperor not to over indulge himself in the sensual pleasures of palace life but to go out and be with his people. I can only imagine the conflict and argument that would have arisen between the inward and outward facing hou, an eternal tug of war.

While the hou guided the comings and goings of the emperor the “jade dew” collected in the dishes, when imbibed by the emperor, ensured him a long life.

My detailed ‘examination’ of the huabiao took place on the day I visited the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall and my camera was back in the hotel. As such, while the first rather poor picture attached is mine, the second one is courtesy of chinapictures.org and the third is from Wikipedia.

This blog entry is one of a group (loop) of entries based on a number of trips to Beijing. I suggest you continue with my next entry – Tiananmen Square – Lowering the Flag – or to start the loop at the beginning go to my Beijing Introduction.

Yes China is full of symbols and meanings. In the old days (really old like 2000+ years back), emperors were appointed on merit. While that morphed into hereditary dynasties, there is still the mandate of heaven. So all kinds of symbols remain to remind the man who ruled all beneath the sky to be a just and moral ruler

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is very difficult for an outsider to understand even a fraction of the symbolism in China. I wonder how much of the younger Chinese people are learning and how much is being lost.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is afterall quite complex!

LikeLike