Yes, Dear Reader, I am still rambling around in Australia and have not jetted of to Africa for a safari.

Today (and yes, it took a full day) we visited the Monarto Safari Park, about fifteen kilometres from where we were staying in Murray Bridge, South Australia. Dedicated to African and indigenous Australian animals (with a few species from other locations) the park covers some 1,500 hectares with about a fifth of that accessible to the public. It is billed as the world’s largest safari park outside of Africa giving the animals loads of space to move around.

Upfront, I will say that I am an animal lover and strong supporter of quality zoos, in particular large open range ones like this where the animals are not enclosed in tiny cages or made to perform for the amusement of visitors. I am well versed in the arguments against zoos but on balance I believe that well run and maintained they are invaluable in educating people about, and exposing them, especially children, to animals they might never otherwise get to see. I know my love affair and care for animals started with my visiting zoos. Alas, not everyone can afford to go on African safaris, visit Antartica, or otherwise interact with animals in their natural habitats.

The conservation work carried out at and by Monarto Safari Park is second to none.

While large the park is split into numerous enclosures so, unlike in a ‘real safari park’, the animals do not hunt or feed on each other and the visitor is pretty much guaranteed to see/ get up close to the them.

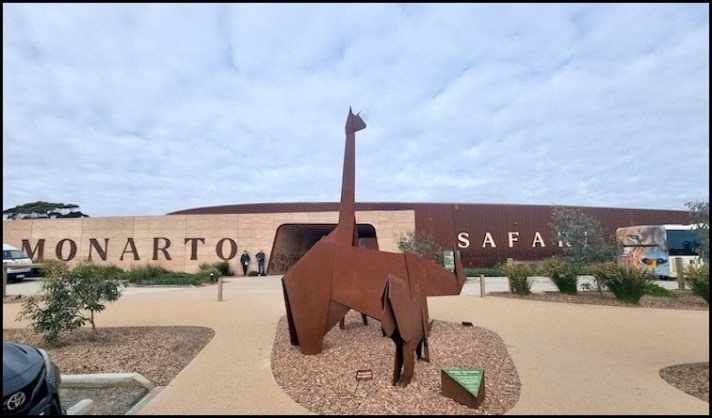

The Safari Park’s new entrance building – encompassing a ticket office, cafe and excellent gift shop.

Given the size of the park the primary way of getting around is via a fleet of busses which operate at fifteen minute intervals (more frequently when busy) throughout the day. This is supplemented by a network of walking tracks, some 12 kilometres in length. While the buses drive through enclosures the walking tracks, hopefully for obvious reasons, skirt along the outside of the enclosures.

The bus route through the park has seven stops (again outside the enclosures!) where one can alight and visit viewing platforms, listen to keeper talks and do some of the shorter walks in the area around each stop. Between stops we took the bus as firstly it gets you up closer to the animals and secondly the guides thereon provide an excellent commentary.

Now for a pictorial view of our visit to Monarto Safari Park (divided across two entries – Part 1 and Part 2).

Scimitar-horned Oryx

These antelope from North Africa are characterised by their large sweeping curved horns which resemble a scimitar sword. Sadly these beautiful animals are now extinct in the wild due to uncontrolled hunting, drought and agricultural encroachment coupled with excessive grazing of the limited vegetation in their natural habitats by domestic livestock. Today they only continue to exist thanks to zoos and parks like Monarto. While the park got its first oryx in 1989 it wasn’t until 2011 that it acquired a sufficiently large mixed sex group of oryx such that it could start a breeding programme. Since 2011 over 50 calves have been bred.

Scimitar-horned Oryx

The ever adorable and inquisitive Meerkat

The meerkat is a type of mongoose that inhabits dry regions of short grass and sparse woody scrub of Africa. They are not a threatened species.

They live in large family groups and start each day by basking in the sun and grooming each other. The rest of the day is spent foraging for insects unless it is their turn to be on sentry duty. Typically those on sentry duty climb to the highest point around to watch for predators and thus protect the group.

A meerkat keeping watch

A novel ‘plaything’ at the former park entry

Yellow – footed Rock-wallaby

The Yellow-footed Rock-wallaby can be seen (with great difficulty given how they blend in) on rocky outcrops and caves in semi-arid country in South Australia where only about 2,000 are thought to remain and in New South Wales where only 50 to 250 are thought to remain in the wild due to intensive hunting in the past and ongoing habitat destruction due to grazing by domestic stock, feral goats and rabbits. Predation by foxes and feral cats is also an issue for the species.

Despite their own limited numbers, the Yellow-footed Rock-wallaby plays an important role in a highly-successful wallaby cross-foster programme. Under this programme critically endangered Victorian Brush-tailed Rock-wallaby joeys are removed from their mother and fostered by a Yellow-footed Rock-wallaby allowing the Brush-tailed Rock-wallaby (only around 60 remaining in the wild) to give birth to another joey approximately 30 days later increasing the amount of offspring one particular female can produce in a year.

Chimpanzee

Chimpanzees are our closest living relative sharing approximately 98.7% of our DNA.

Chimpanzees are classified as an endangered species with approximately 150,000 to 300,000 chimps remaining in the wild. The major threat to chimpanzee is habitat loss due to logging, mining, palm oil plantations and population growth. They are also hunted for the bushmeat trade with young chimps being sold as pets for entertainment.

Due to the genetic similarity between chimpanzees and humans, chimpanzees are highly susceptible to human diseases. As human populations grow, diseases such as Ebola, polio, and even the common flu can have a devastating impact on entire chimpanzee communities. Yes, chimpanzees are susceptible to Covid-19.

A penny for your thoughts?

A baby chimp, just a few weeks old with mum. I wonder if that is the proud dad alongside with the smirk on his face!

A couple of lovebird interlopers not on the park’s payroll!

Malleefowl

Found in southern parts of mainland Australia in mallee habitat with light tree cover for camouflage, malleefowl require lots of leaf litter for foraging and for use as material for building and maintaining their huge nesting mounds on the ground. When needed, the male bird digs an egg chamber into the mound and the female lays an egg every 5-7 days. When the laying is complete the male covers the mound with twigs for extra protection. These mounds (pictured below) can be up to a meter high and up to five meters in diameter.

The heat from the composting vegetation incubates the eggs. During the incubation period the male monitors the temperature in the mound removing or adding additional sand/loam and leaf litter to keep the temperature at a constant 33 degrees centigrade.

Per Wikipedia

Hatchlings use their strong feet to break out of the egg, then lie on their backs and scratch their way to the surface, struggling hard for 5–10 minutes to gain 3 to 15 cm (1 to 6 in) at a time, and then resting for an hour or so before starting again. Reaching the surface takes between 2 and 15 hours. Chicks pop out of the nesting material with little or no warning, with eyes and beaks tightly closed, then immediately take a deep breath and open their eyes, before freezing motionless for as long as 20 minutes.

The chick then quickly emerges from the hole and rolls or staggers to the base of the mound, disappearing into the scrub within moments. Within an hour, it will be able to run reasonably well; it can flutter for a short distance and run very fast within two hours, and despite not having yet grown tail feathers, it can fly strongly within a day.

Chicks have no contact with adults or other chicks; they tend to hatch one at a time, and birds of any age ignore one another except for mating or territorial disputes.

A Malleefoul mound

What do you see below?

Answer : A Tawny Frogmouth

I imagine we must have startled this one as typically when feeling threatened they imitate a broken branch and freeze with their bill pointed upwards and their eyes closed to slits. While generally nocturnal and carnivorous and looking like owls Tawny Frogmouths are not owls.

A small herd of red deer resting in the shade

Przewalski’s Horse

A Przewalski’s Horse, or P-horse for short, is the world’s only remaining wild horse and is native to Mongolia, Kazhakstan and the Gobi Desert.

Przewalski’s Horses were once classified as extinct in the wild. However in 1995, Monarto Safari Park participated in a programme which saw seven horses successfully reintroduced to Takhi Tal Nature Reserve in Mongolia, leading to the species forming functional breeding herds in its native habitat. As a result, in 2008 their status was downgraded from extinct to critically endangered.

American Bison

It is rather ironic that American Bison were the first species to arrive at Monarto Safari Park (in 1983) which today specialises in African and Australian species.

Tens of millions of American Bison once dominated the grassy plains of North America, however during the 19th century commercial hunting, habitat loss and bovine diseases drastically reduced their numbers, almost to the point of extinction.

The American Bison population has today partially recovered with an estimated 15,000 animals remaining in the wild.

Black Rhinoceros

Monarto Safari Park is currently one of only two Australian zoos that house the magnificent Black Rhinoceros.

The Black Rhinoceros is classified as critically endangered with as few as 2,500 to 3,000 thought to be living in the wild today. Once found living throughout southern, central and eastern Africa they’re now only found in very isolated, protected areas of South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe and Kenya.

In the 20th century the black rhino was the most common rhino species found in Africa, however as a result of poaching for the illegal horn trade, it’s estimated that the black rhino population has declined by 97% since 1960.

Black Rhinoceros

I will continue my review of Monarto Safari Park in a seperate review.

I would like to credit the Monarto Safari Park website (https://www.monartosafari.com.au/) from which I gleaned much of the detail in this review.

The next review from my Adelaide to Canberra road trip can be found HERE .

Should you wish to follow this road trip from the beginning please start HERE.

A very interesting read with great photos, Albert! I know everyone isn’t a fan of zoos, safari parks or aquariums, but many that I have been to during my travels have been rewarding experiences. And, as you say, of the many benefits that such places offer are that had it not been for them it would be unlikely that I would ever have seen some of those animals in the wild. Care, and careful breeding programs benefit the animals too. Imagine if there was a real “Jurassic Park” — kind of a scary thought though, wouldn’t you say?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for visiting Sylvia.. What you say is spot on and a real Jurassic Park, a scary thought indeed.

LikeLike

This zoo seems to have all the right credentials for me to spend a whole day there too Albert. Great photos by the way.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Malc. This is an easy and accessible way to see these beautiful animals in environments as close to their natural habitats as is possible.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful! Like you I’m an animal lover AND fan of good zoos and safari parks etc. – I don’t see a conflict there 😀 And this one looks excellent and seems to be doing some great conservation work. I was interested to read about the Malleefowl as I’ve never heard of them, but my favourites are the rhino, the meerkats and of course the baby chimp!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Sarah, Monarto is one of the best … There is another similar concept park in Dubbo, NSW which I equally love.

LikeLiked by 1 person