This morning we left South Australia and crossed the state border into Victoria. Rather than the colourful state borders signs I have encountered elsewhere in Australia, at this crossing the ‘welcome’ was a serious of signs warning us that speed cameras were in operation though-out Victoria. Well, I guess we can’t later say we were not forewarned should we transgress.

Also, upon crossing the state border, we had to adjust our timepieces by moving them forward half an hour. South Australia is one of only a handful of jurisdictions in the world that defies the international norm of using hourly offsets from Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) or Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), if that is what you prefer.

Interestingly, at least for me so bear with me, is that North Korea was, perhaps not surprisingly, another defier. North Korea established ‘Pyongyang time’ in 2015 by setting its time to 8½ hours ahead of GMT. In doing so, it moved away from Japanese time, a legacy of Japanese colonial rule from about a century earlier. Unfortunately, this put North Korea on a different time than South Korea. In 2018, North Korea scrapped ‘Pyongyang time’ and returned to the same time as South Korea (and Japan), officially to promote intra-Korean relations and push the country towards reunification – an act of unilateral brotherly love! Anyway, I have digressed, so back to Victoria and our next stop in the Murray-Sunset National Park but before I do – shameless plug – have you read my posts on my two visits to North Korea, one in 2014 and one in 2018? They can be found HERE and HERE.

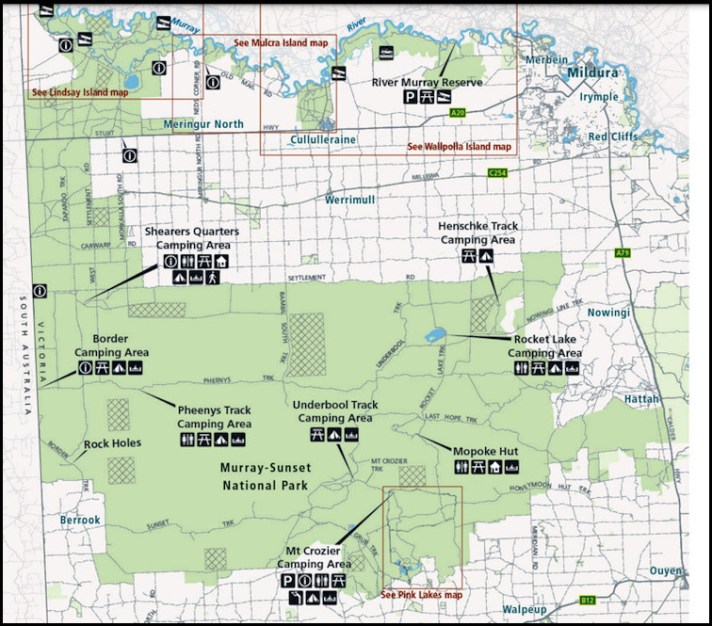

At 6,330 square kilometres , the Murray-Sunset National Park is the second largest national park in the State of Victoria. It is located in the Mallee district in the northwestern corner of the state.

The park is one of the last remaining semi-arid regions in the world where the environment remains relatively untouched (apart from some former salt harvesting which I will come to later). Needless to say, in the couple of days we spent there, we only visited a very small part of the park – its famous Pink (salt) Lakes section.

The Pink Lakes are so named because of their colour – especially from late summer to spring, making our winter visit perfect timing. The pink colouring comes from a red pigment, carotene, secreted from the algae. The colour is best seen early or late in the day or when it is partially cloudy.

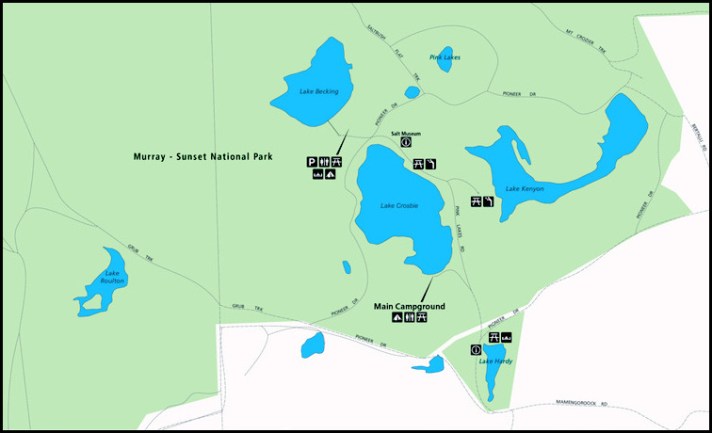

We chose to stay at the main (Lake Crosbie) campground, the largest and most accessible of the campgrounds in the Pink Lakes area. Like many National Park campgrounds in Australia, it is laid out in a way more appropriate to the 1970s, meaning that getting into a spot can be difficult for today’s larger rigs. Driving around, we identified two prime sites, either of which we would have loved to have if they had been free, which they were not. As it was, we had to awkwardly squeeze into a third site where a metal post planted smack in the middle of the area prevented us from positioning the van where we would have liked it. We decided to remain hooked up (i.e. not unhitch the van from the car) for the first night in the hope that one of our two preferred sites would become available the following morning.

Our site, with the rear of the van as opposed to one of the sides, facing the view. Nonetheless a nice spot.

Our view from camp, pretty good.

Having settled in and had some lunch and a short rest it was time to get out and explore.

There are a number of walks laid out in the Pink Lakes area and today we decided to do the longer (5kms) Kline Loop nature walk as it started at our campground. Tomorrow we will unhook the car, irrespective of whether we get another site or not, and explore a little further afield.

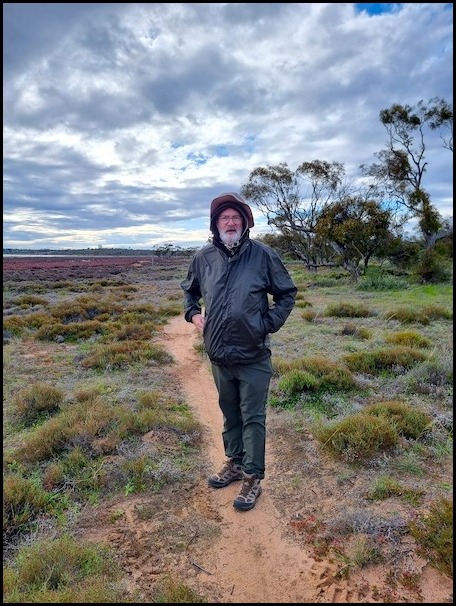

Well wrapped up for the walk. I am not sure why I needed three levels of head protection!

We were blessed with perfect conditions for photographing the lakes in all their pink glory…. a very ‘moody day’ – cold, hot, cloudy and sunny. I am at best a rather average photographer but was very happy with the shots I managed to get here. We didn’t carry the drone on today’s walk but did take it the following day – it really is the best way to capture the lakes in all their colourful glory.

Kline Loop walk is a well marked walk, named after a former worker who lived and worked in the area in the 1930s and 1940s. It took us along the eastern edge of Lake Crosbie before crossing pine-wooded rises to the picturesque Lake Kenyon and then back via a former salt mining site which provided a fascinating insight into a back-breaking venture of yesteryear.

In the main I will let my photos speak for themselves on this walk.

Along side Lake Crosbie

Along side Lake Crosbie

Along side Lake Crosbie

My lead picture above is also of Lake Crosbie. I was taken the following afternoon from a viewing platform on the north side of the lake.

Across the rise and overlooking Lake Kenyon

Across the rise and overlooking Lake Kenyon

Lake Kenyon

Old salt harvesting equipment by Lake Kenyon

Lake Kenyon

Lake Kenyon

Given the amount of rainfall in recent times we were forunate to find all the lakes pretty much full – a rare occurence. Generally these salt lakes lakes evaporate over summer leaving concentrated salt crusts over black mud. This residue can be seen above and in more detail in the next two pictures.

Salt residue left as the water in Lake Kenyon evaporates

Salt residue at Lake Kenyon

Lake Kenyon

A final look at Lake Kenyon before we headed back over the hill to the ‘salt museum’.

Abandoned vehicle between Lake Kenyon and Lake Crosbie

More abandoned salt harvesting equipment between Lake Kenyon and Lake Crosbie

Heading back to Lake Crosbie

Old salt harvesting equipment with old salt stock piles to the rear at what is now referred to as the salt museum

Old salt stock piles left after harvesting finished here in 1979

Commercial salt harvesting began, spurred on by an increased demand for salt during World War I, in the Pink Lakes area in 1916, using shovels and wheel-barrows in temperatures often exceeding 40 degrees centigrade in the summer harvesting season. As much as 500 tons of raw salt was scraped from the lakes in a day during peak production times or around 10,000 tons in a season – a years supply of refined salt for 3 million people, at 10mgs per day.

For more than twenty years, until replaced by trucks, camel teams transported the salt away from the area. Salt mining continued, post-WWII, under the auspices of Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI), until the area was declared a State Park in 1979. In 1991 the State Park was incorporated into the Murray-Sunset National Park.

Having had a good look around the ‘salt museum’ we made our way back to camp, along the eastern shore of Lake Crosbie

And what better way to end the day than admire the beautiful sunset, after which the Murray-Sunset National Park is named.

The next review from my Adelaide to Canberra road trip can be found HERE.

Should you wish to follow this road trip from the beginning please start HERE.

That’s not something you would have seen every day in Northern Ireland Albert.

I don’t know why, but I’ve always had a fascination for salt lakes, and these are something else. Those colours are unbelievable and your photographs capture them perfectly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Certainly not Malc. Like you I find them fascinating and the colours amazing.

LikeLike

How interesting to see a pink lake!

LikeLiked by 1 person

They really are beautiful in the right light which I had.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, amazing colours and I love the two shots of the salt crusts from above 😮

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Sarah.. there will be a few drone shots in my next entry which really show how amazing these lakes are.

LikeLiked by 1 person